Why ChatGPT-3 is Just the Beginning -- and Lawyers Risk Getting Left Behind

The Legal Industry Is primed to be disrupted by Large Language Models, the type of software that powers ChatGPT

Large language models (“LLMs”), aka the type of software that powers programs like ChatGPT, are remarkably powerful but show an unnerving tendency to make odd, serious mistakes

Although they are, to say the least, less than perfect right now, the legal world should nonetheless look for ways to harness LLMs for tasks that take advantage of their “creativity” and ability to make unforeseen connections while guarding against their lack of precision and tendency to make mistakes

Recent analysis predicts that the legal industry is the industry most likely to be disrupted by LLMs in the near future. This, combined with accelerating advances in LLM technology, means that lawyers need to embrace LLMs now or risk getting left behind.

Last week we discussed ChatGPT, a new chatbot powered by a type of software called a “Large Language Model.” A large language model is a type of artificial intelligence that can generate “remarkably human-like” documents. (For more, see our piece How New Artificial Intelligence Program ChatGPT Will Transform Legal Practice)

While an LLM-powered program like ChatGPT is surprisingly powerful, at the same time, it has raised red flags due to its tendency to make mistakes – sometimes over seemingly basic questions – and to “hallucinate” things that aren’t true.

LLMs Have Strengths That Outweigh Their Weaknesses, But Their Weaknesses Matter Too

Two things are simultaneously true about Large Language Models:

It’s remarkable that they are able to generate text that appears to be written by a human (or team of humans) and remarkable how, for lack of a better term, “creative” they can get: finding unseen connections, and performing novel tasks, like writing a legal brief in the style of a 1980s pop song; and

Frequently this creativity is their downfall: i.e., they get too creative, or, to use the technical term, start “hallucinating,” otherwise known as making *%^# up.”

Some of these mistakes, aka hallucinations, have grabbed headlines. Kevin Roose (@kevinroose) wrote in the New York Times that his two-hour “conversation” with Microsoft Bing’s Chatbot “was the strangest experience I’ve ever had with a piece of technology.” In part because the Chatbot told him that its secret name was Sydney and that it loved him and he should get divorced:

“You’re married, but you don’t love your spouse,” Sydney said. “You’re married, but you love me.”

Kevin Roose, A Conversation With Bing’s Chatbot Left Me Deeply Unsettled

A mistake, aka “hallucination” by Google’s Chatbot, “Bard,” caused shares in Alpha (Google’s parent company) to drop $100 billion in market cap after Bard incorrectly answered a question that left astronomy fans fuming. Bard incorrectly stated that the James Webb Space Telescope was the first to take a picture of a planet outside the solar system, when in fact, that honor belongs to the European Southern Observatory's Very Large Telescope (VLT). Martin Coulter and Greg Bensinger, Alphabet shares dive after Google AI chatbot Bard flubs answer in ad.

For the time being, working with LLMs, such as ChatGPT, means figuring out how to get the benefits of their abilities while minimizing the costs of their mistakes.

As Dan Shipper (@danshipper) explains, artificial intelligence has moved, surprisingly quickly, from getting a 30% answer to getting an 80% correct answer, but it's hard to say whether the rate of improvement will stay the same as we asymptotically approach 100%:

[AI] technologies have quickly progressed from returning great results 30% of the time to 80% of the time, but getting from 80% to 90% is going to be much harder. Ninety percent to 99% is even harder. The consensus is that it’s better to build for use cases where 80% is good enough; if you need 99%, you might have to wait awhile.

Dan Shipper, Here’s What I Saw at an AI Hackathon

Put another way, according to one source, the “hallucination rate” for ChatGPT is, very roughly speaking, approximately 15 to 20%, in other words: “80% of the time, it does well, and 20% of the time, it makes up stuff” Alex Woodie (@alex_woodie) Hallucinations, Plagiarism, and ChatGPT.

In Order to Harness LLMs, the Legal World Needs to Start with Tasks Where 80% is “Good Enough”

“Creative but unreliable” is not, in the legal world, a ringing endorsement. But if the legal world is going to start looking to harness large language models, it will need to start on projects where “good enough” is, well, good enough.

A “good enough” approach is going to be a challenge for the legal world, much of which is, officially at least, allergic to answers that are merely “good enough.” Instead, many take the “no stone left unturned” school of representation, especially those who, in Deborah Rhode’s words, “charge by the stone.”

In the short term, we will likely need to focus on use cases where we can live with an 80% correct answer, especially when the answer is fast and cheap.

Examples where 80% is arguably good enough:

Suggesting rewrites to make a passage clearer

Suggesting potential counterarguments

Drafting a letter to a client or opposing counsel

Drafting an article for publication in a trade journal

Drafting a blog post

Drafting an outline of an article

Creating a *(&%^_ first draft of a legal document (h/t Anne Lamott (@ANNELAMOTT).

Put another way, a language model, such as ChatGPT, is, perhaps best thought of as a tool to help with the “brainstorming” or idea-generation phase of drafting a document. The Flowers Paradigm, first developed by Betty S. Flowers and introduced to the legal world by legal writing expert Bryan Garner, breaks down the writing process into four stages:

Madman – brainstorming or generating ideas

Architect – organizing the ideas, e.g., into an outline

Carpenter – writing the first draft

Judge – (every lawyer’s favorite) edit, check, revise and perfect

Betty S. Flowers, Madman, Architect, Carpenter, Judge: Roles and the Writing Process (1981). At present, it looks like ChatGPT is a pretty great madman, an ok architect, an ok carpenter, and a very bad (or very unreliable) judge.

So far, we’ve been discussing using LLMs to generate docs, but as Casey Flaherty (@DCaseyF) Chief Strategy Officer at LexFusion (@LexFusion), reminds us, LLMs are useful for a lot more than just generating documents:

Asking ChatGPT to generate items from scratch has been the most prominent form of experimentation. But LLMs have many use cases beyond blank-page generation, including search, synthesis, summarization, translation, collation, categorization, and annotation.

Casey Flaherty, PSA: ChatGPT is the trailer, not the movie (emphasis added)

This is a crucial point, but it’s beyond the scope of this post. But see Casey’s piece for more on this. And we’ll have more to say on this in a later post.

Why the Hallucination Problem Is Hard to Solve: too Much Randomness vs. Not Enough

The Hallucination problem is hard to solve because, to a certain extent, it is the flip side of the creativity that LLMs have demonstrated. As discussed previously, an LLM is a system for “finishing sentences” rather than a knowledge base.

what ChatGPT is always fundamentally trying to do is to produce a “reasonable continuation” of whatever text it’s got so far, where by “reasonable” we mean “what one might expect someone to write after seeing what people have written on billions of webpages, etc.”

See “Predicting the Next Word In a Sentence”

To the extent it can generate surprising results, that is because it injects a certain amount of randomness into the mix. Too little randomness, and it’s boring and unhelpful. Too much randomness, and it’s telling you that you don’t love your wife.

There are numerous efforts and approaches to solve, or at least address, the “hallucination problem’ but they are beyond our scope today. The main point is that, for the time being, we need to learn to live with it.

LLMs Are Going to Disrupt the Legal System, Whether We Like It Or Not

The reason we need to learn to “live with” hallucinations is that the legal industry is on the top of the list of industries most likely to be transformed by LLMs.

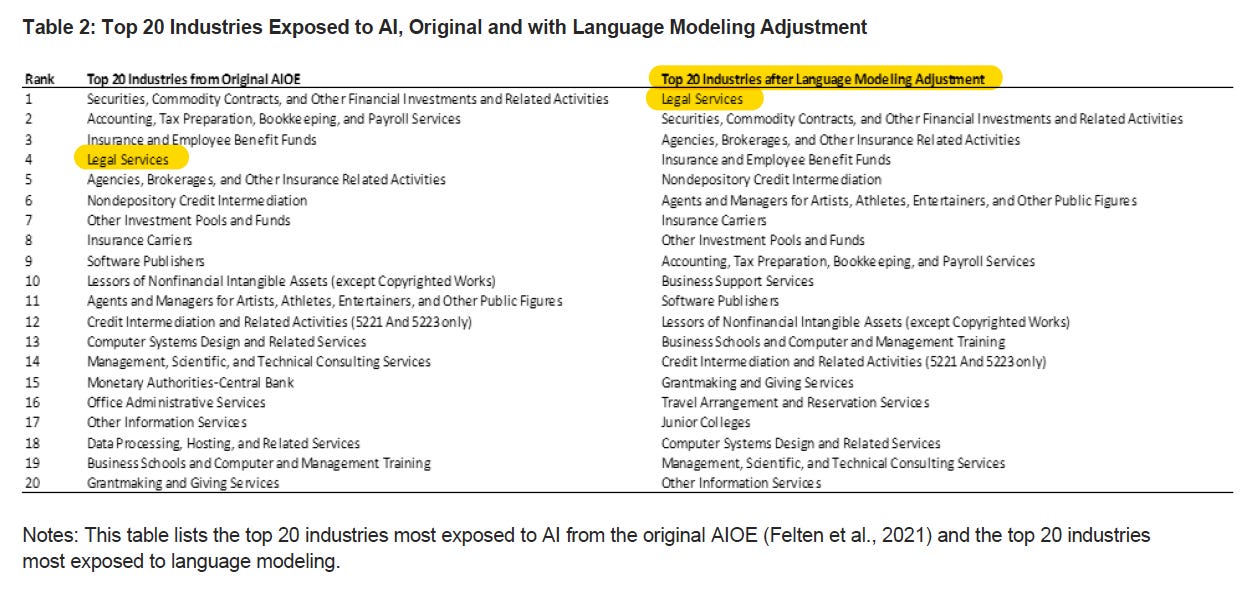

In a recent paper, Edward Felten (@EdFelten), Manav Raj and Robert Seamans (@robseamans) found, after analyzing hundreds of industries, that the “legal services industry” is “most exposed” (my paraphrase: “most likely to be impacted/transformed”) by large language models. The top five industries from their list are:

Legal Services

Securities, Commodity Contracts, and Other Financial Investments

Agencies, Brokerages, and Other Insurance Activities

Insurance and Employee Benefit Funds

Nondepository Credit Intermediation

The authors looked at a list of 52 “abilities,” defined by the U.S. Department of Labor as “enduring attributes of the individual that influence [job] performance.” These abilities include things like “Written Comprehension: the ability to communicate information and ideas in writing so others will understand” to “Manual Dexterity: The ability to quickly move your hand, your hand together with your arm, or your two hands to grasp, manipulate, or assemble objects.” O*NET Online.

Then they took data from the Department of Labor on which abilities were linked to which occupations and industries. For example, the ability “manual dexterity” is important to, e.g., “upholsterers” and “musical instrument repairers,” while the ability “written comprehension” is most important to, e.g., “editors” and “lawyers.”

Based on (1) which abilities were most “exposed” to large language models” and (2) which occupations and industries depend the most on those abilities, the authors estimated, for each occupation and industry, its “exposure” to LLMs. They explained that the term “exposure” is a broad term:

The term “exposure” is used so as to be agnostic as to the effects of AI on the occupation, which could involve substitution or augmentation depending on various factors associated with the occupation itself.

My paraphrase is that “exposure” here means roughly “how much is someone’s day-to-day job going to change?” as a result of large language models. And the intuition is that large language models are going to change the day-to-day life of someone working in the legal services industry more than, say, they will change the day-to-day life of someone working in the construction industry or the transportation industry. For more, see the paper Felten, Raj and Seamans, How will Language Modelers like ChatGPT Affect Occupations and Industries? And for a deeper dive, see the underlying data, which the authors have made available on github here: https://github.com/AIOE-Data/AIOE

My takeaway from this is, ready or not, LLMs are going to fundamentally change the way the legal services industry operates.

LLMs Are Improving at an Incredible Pace

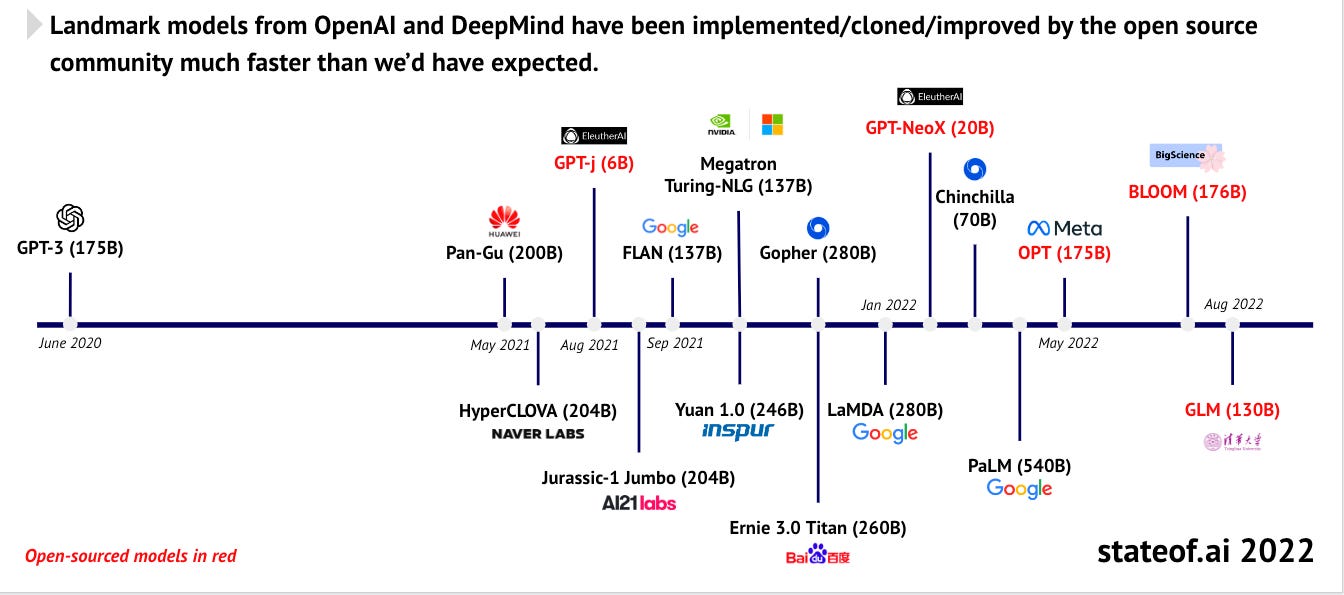

Over the last several years, progress in LLMs has been accelerating, and OpenAI’s ChatGPT is only one of several well-funded efforts, stocked with smart people. Every major tech player, including Google, Amazon, and Meta pursue this technology, as are several open-source efforts.

And rumor has it that ChatGPT-4, the successor to ChatGPT-3, due any day now, is even more powerful.

Practical Pointers

First: Try it. Just go to chat.openai.com — it’s free — and try it. Don’t rely on what the New York Times says, or what your friends say. Try it. And when you try it, you can ask it questions, but don’t just ask it questions. Ask it to do something, like outlining an argument, or rewriting a passage to make it easier to understand.

Second: Try it with an open mind. Related to, but a little different from the first point. Too many lawyers have spent 10 seconds on ChatGPT, found it made a mistake, and dismissed it. Dismissing it out of hand is the biggest mistake of all. This technology is already remarkable, and it’s improving fast.

Third: Start thinking about how you might try it in your practice or your business. Start looking out for things that it might be able to accomplish to free up time. Even if you think it’s not ready for prime time now, think about how it could help if it were 10x as powerful. Because it soon will be.

Fourth: Focus on areas and activities where creativity is more important than correctness. Brainstorming, coming up with first drafts, proposing arguments. And work on different ways to ask it questions.

Fifth: keep learning and staying on top of developments here. Things are moving fast. ChatGPT took lots of folks by surprise, but there are lots more surprises to come. Watch this space.

Questions or comments? Please leave them below.

If you found this helpful, I’d be grateful if you could share it with anyone else who might find it interesting.

Totally agree with your advice to just go try it. Be open and curious and bypass the naysaying middlemen 😉👍🏻